Will Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT change how mathematics is done? When earlier computing technologies came along, they resulted in major changes in how we do mathematics: mechanical and then electronic calculators, general purpose digital computers, graphing calculators, etc. and more recently tools such as Mathematica, Maple, and (my favorite) Wolfram Alpha.

The latter three above can all lay claim to being a special kind of “artificial intelligence”, though as with chess-playing systems, the highly restricted nature of the domain means we don’t generally classify them as such. But here’s the point. Those products already do all procedural mathematics, so there is (almost – read on) nothing left for new AI systems like ChatGPT to do that we don’t already have.

Certainly, if you take an LLM and connect it to a system like Wolfram Alpha, you get a powerful tool. As reported by Conrad Wolfram in March of last year, that combo scored 96% in a UK Maths A-level paper. That’s the exam taken at the end of school, as a crucial metric for university entrance.

What ChatGTP did was convert the questions on the test into the form where they could be solved by Wolfram Alpha. Given the correct input, Alpha will give the correct result every time. So credit for that 96% score should go to Alpha. The 4% error was presumably due to ChatGPT screwing up the interpretation of some questions.

But will LLMs on their own have a big impact? Here, things are far less clear cut; in fact, using an LLM to answer a math problem is probably best avoided. In that UK study I cited above, ChatGPT scored a mere 43% when given the A-level questions to answer on its own.

That poor performance is hardly surprising. LLMs are, as the name suggests, language processors. Basically, they look at what you enter and trawl through a massive database of Web-based text to see what the most likely next letter or groups of letters is, and iterate on that. There is, to be sure, more to it; for one thing they use traditional natural language processing algorithms and other AI techniques to decide what kind of response you are looking for. But the core technique is finding the best guess of what comes next and spitting that out. It’s tech-bro mansplaining writ large. The linguist Emily Bender has referred to them as “stochastic parrots”, a description I find particularly apt.

In particular, the LLM has no machinery to determine truth or factuality. That’s why LLMs so frequently “hallucinate”, that is, produce output text that reads smoothly but is totally false.

In contrast, mathematics is a discipline that is all about truth: mathematical truth (based on axioms) in the case of pure mathematics, and factual truth when we apply mathematics to the world.

For all its abstraction, however, mathematics is firmly rooted in the physical and social world. Its fundamental concepts are not arbitrary inventions; they are, indeed, abstractions from the world.

That process of abstraction goes back to the very beginnings of mathematics, with the emergence of numbers around 10,000 years ago in Sumeria. I recounted that history in an online presentation for the New York based Museum of Mathematics on June 28 last year. You have to pay MoMath to view it (or the entire four-part series it was part of), but supporting the museum is a worthy cause!

Historically, numbers are the most basic mathematical abstractions. Though the numbers we use today, including the counting numbers — often introduced to children as points on a number line — are a late 19th early 20th Century creation, for most of history, counting numbers were multitude-species pairs having their origin in monetary systems (as with our “4 dollars and 90 cents” currency numbers). The transition from those early numbers into today’s pure abstractions took many centuries. (Negative numbers were not accepted as bona fide mathematical objects until the 19th Century.)

The many abstract entities of modern (advanced) mathematics, such as groups, rings, fields, Hilbert spaces, Banach spaces, and so on, are all connected to the real world by towers of abstractions. For all its seemingly esoteric nature, mathematics is firmly rooted in the real world. That’s why mathematical results can be applied to the real world; for example, theorems about geometric structures of dimension 4 and greater can be (and are) applied to solve real-world problems about communications networks, transportation networks, and efficient data storage.

Though we mathematicians are comfortable working within that world of abstractions, we achieve that comfort by first (as students) ascending the towers, which means the meanings we ascribe to the concepts are grounded in reality — even if we are not consciously aware of that grounding. (Mathematicians, perhaps more so than many other people, are very aware of how little we understand what is going on in our minds, even when deeply engaged in problem-solving thought. That recognition is forced on us every time we get a breakthrough idea “out of nowhere”!)

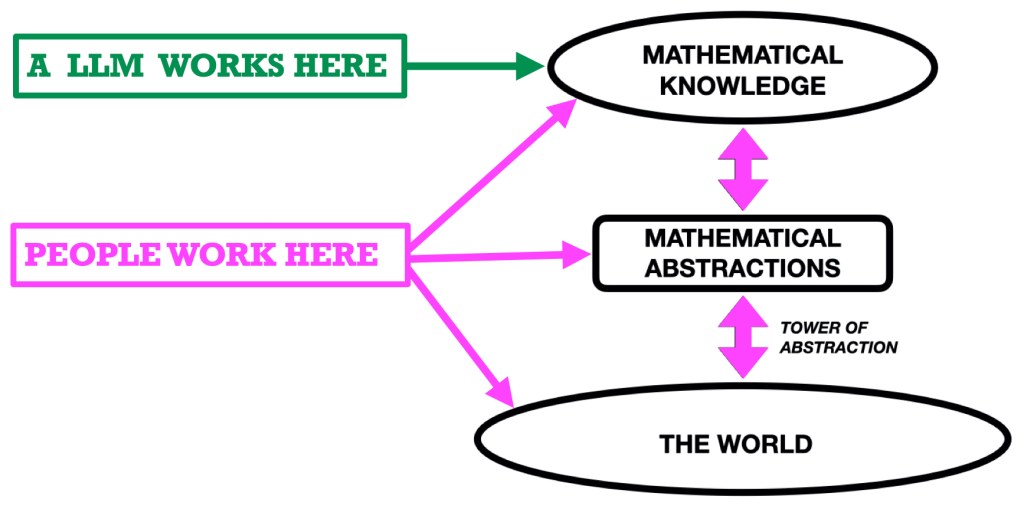

Mathematics is, then, a semantic enterprise engaged in by creatures/minds that are deeply and fundamentally connected to reality, and which have motivations, desires, curiosity, and a drive to understand both the world and one another. In terms of the figure, we operate in the entire space shown in that landscape. Mathematical knowledge results from activity we engage in as such creatures using the concepts and methods that we and our predecessors have abstracted from the world.

LLMs, in contrast, operate exclusively in the upper region, MATHEMATICAL KNOWLEDGE. They process text. Not meanings, text (i.e., strings of symbols). Whereas we humans can make advances by seeing patterns in the semantic entities we are studying, LLMs (implicitly) discern patterns in the symbols they process. Those patterns reflect the popularity of the symbols in a vast corpus of text produced by humans (and, increasingly, their own earlier productions and those of other LLMs, which may turn out to be a major problem for them and us).

[In a follow-up post, I’ll summarize current thinking in cognitive science about how we think — about mathematics, or anything else for that matter — to highlight just how different our thinking is from how LLMs work.]

For the most part, the productions of LLMs are correct because most of the texts they draw upon are correct — especially if the LLM is restricted to draw on sources that have passed through some form of review and editorial control. (Is this the case?) But as is already now well known, they can produce outputs that seem sensible but on examination are total nonsense.

This, I think, is a major weakness in LLMs as “thinking machines”. Even when our head is in the mathematical clouds, we humans have our feet firmly on the ground. (Metaphorically; many of us curl up on a comfy chair to ruminate.) We are living creatures of the world and we are an interactive part of the world, with brains that evolved to act in, react to, and think about the world. We think in meanings. An LLM inputs and outputs strings of symbols. Period. Those are vastly different kinds of activity.

The fact that we can give meaning to LLMs’ outputs reflects our cognitive abilities, not theirs; they are just doing what we built them to do. (Much like the clocks we build; a clock does not have a concept of time; we construct clocks so that we can interpret their state as the time.) Using words like “intelligence” or “thinking” for AI systems is a category error. LLMs do something different from us. (Think of them as a very fancy analogue of a clock, designed to report on the current state of the human knowledge stored on the Internet.) We should view them as such.

If you use an LLM to work on a math problem where the answer you get has any significance for you or anyone else (e.g. you are an engineer working on the design of a bridge), you need to be sure you have the ability to detect that the answer is wrong.

That critical caveat aside, I am intrigued by the possibility that a LLM will detect a pattern in the vast corpus of mathematical knowledge on the Web that we humans are unlikely to discern. It’s not impossible (though perhaps highly unlikely) that an LLM could produce an original result this way, giving the world its first “LLM’s Theorem”.

More likely, I think, we mathematicians could use an LLM to make us aware of (human or written) sources we did not know about. (LLMs as “dating apps for mathematicians trying to prove theorems” anyone?) We can of course do that already using a search engine; indeed, many of us use Google as a first port-of-call when starting on a new problem, for precisely that reason. But the LLM brings something new: the capacity to discern syntactic (i.e., symbolic) patterns in the vast corpus of written mathematics that humans are (for reasons of scale, if nothing else) not capable of discerning. Many of those patterns may turn out to have no mathematical import. But some may. That’s something we have never had before.

But this possible use of LLMs is available only to experienced mathematicians. For everyone else, I’ll repeat my above caution: avoid their use in mathematics unless you are sure you can detect a wrong answer. Because there is a real possibility you will get a doozy.

NOTE: This post is a much shorter version of an essay I published in the MAA blog Devlin’s Angle in March.